NO. This is something completely different--and will likely be more maddening.

But--YES. This is what we (often) do here. We question the monolith via a "termite art" application of analytical techniques (which only rarely involve sawing our lovely assistant in half).

So here we go (again). We'll be sneaking up to this one, even though the punch line is telegraphed in the blog post title.

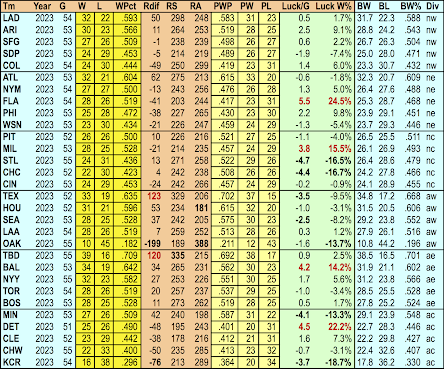

AT right you'll see the "standard standings" (minus the "games behind" column) that you'd see in either print or online media this morning--the basic record of MLB action up to and including games of 5/28/23.

Except that if you look at it closely, you'll see that it isn't quite right (at least not in the standard, accepted sense). There are a couple of teams that are not quite in the right place relative to their WPCT.

That's because we "blended" the basic standings info with its analogue, the Pythagorean Winning Percentage (PWP), and resorted the unseen portion of the table according to such a "blended" approach.

(In case you're unfamiliar with PWP--and if so, thank you, no, we have Jeni's Watermelon Taffy™ ice cream on hand, so feel free to hang onto that bumper crop of "deep-thump" that you rode in on--it's a formula using a ratio of runs scored/runs allowed to predict what a team's WPCT ought to be. Or what the Notorious RGB would have called "the meritocratic won-loss record.")

The shifts induced by this are not earth-shattering, but they might eventually wreak some havoc with the awarding of wild-card slots, which could create some consternation in some quarters.

Before we show the results of the fully "blended" approach on their own terms, however, let's look at how Pythagorean "luck" is distributed in the more interconnected world of MLB (thanks in part to the still highly underreported change to the game in '23--the significant expansion of interleague play). To be frank, the "blended" approach here isn't as far as one could go with it: we could take this all the way to "pureed"--and don't push back too hard, or we will do just that!SO here are the standings shown from the standpoint of Pythagorean luck. It's usually noted in the former of an integer: whole games of luck. But we are imps, and so we've added a later of precision that will permit us to eventually construct a standings system more incomprehensible that stock market derivatives. We then convert that figure into a percentage difference between a team's actual WPCT and its PWP, which gives you the figure in the column at far right ("Luck WPCT", or "Luck W%" as its shown above). And then we sort by that measure, which shows you the current state of luck as it's in play within MLB as of this morning. The Fish and the Tigers are getting away with something akin to murder, while the Cubs and the Royals are the dead bodies that the Clueless ones are trying to match to their murder weapon and murderer.

|

| Liz Scott to El Tiante: "No one makes 'em like you do, Louie!" |

To "blend" these stats (and, as noted, this is just a primitive attempt...) you simply need to average the actual WPCT and PWP. It's not an involved recipe (at least not yet, but be assured that we can make it just as convoluted as the Commonwealth--or the favorite drink of that smoky-voiced femme fatale in Dead Reckoning, the (Pedro) Ramos Gin Fizz.

AND so we blend, and shake, blend and shake, shake, shake (like "the Fizz," we clearly need standings with a copious quantity of foam--to go with the mouth-foam that has regretfully overtaken our age, natch). When we do so, we wind up with non-integer "games" won/lost, which will anger purists and the terminally hip in roughly equal measure (be warned, though, that we could make that measure much more "precise"!).

When we do all that, and stop with all the smark (a blended amalgam of "smart" and "snark"--exact proportions subject to change without notice...) we get the following look at a simple, first-cut pass at "blended" standings.We've set it up by league/division (not wishing to be any more divisive than what we can get away with sans jail time...) so you can see how it coheres to the collision of real wins/losses and the "shoulda coulda woulda" of the Pythagorean alternative.

In this formulation, Pirate fans would be thrilled to see that their long-suffering club would make the post-season if the season came to an end on the day before Memorial Day, whereas Brewers fans would be up in arms, with some wanting to kidnap the governor (oops, sorry, that's Michigan, not Wisconsin). And Mariners' fans would be buoyed by the fact that the blended stats put their team into the post-season ahead of the Red Sox, due to the imperatives of the (so-called) "meritocratic won-loss record."

NOW there naturally are ways (as we've already noted) to make this a lot more complicated, and we've suggested many of them here in past postings where we've dared you to call up the men in the white coats and send them palpitating in our direction. We'll eventually (inevitably?) revisit some of those, and invent a few more, since it appears that 2023 is an entirely appropriate season for such flights of fustian fancy. As noted, the expansion of interleague play opens up several approaches that could exponentially increase the number of worms slithering from the can as we look for ways to loose more mere anarchy upon this little world, this emerald isle of baseball--in truth a cherished little island of hokum in a sea of fatuity, a tiny, mitigated meta-world that might be much more alluring if it would only substitute a funhouse mirror for its two-dimensional looking-glass.

OK. We're snapping our fingers now, and you must determine for yourselves if this now reality, or (merely) a post-hypnotic suggestion...