Apropos of nothing (or, virtually nothing)...the subject of interleague play came up--given that it will become a good bit more ubiquitous in 2023.

That could throw baseball's stats further out of whack in ways that probably won't be measured; so, given that we are at the 25-year marker for this phenomenon (you may dimly recall that it began in 1997...), we decided to look at some of the data tucked away at Forman et fils (you know, Baseball Reference...) while we were waiting for the turkey to emerge from the oven. (And then we were really sidetracked when the bird--as opposed, of course, to "the Bird"--finally emerged...leading to an unusually protracted "turkey coma.")But we are at least semi-awake now: so, first things first: has interleague play evened out over 25 years? (Yes, we know, it's actually 26 years, but we're bypassing 2020 in our calculations due to the abbreviated COVID schedule.) The data at left may shock everyone, even those often-arrogant folks in the "Nor'east Corridor." Two teams are suspiciously better at interleague play than anyone else...

...and those two teams are the Red Sox and the Yankees.

The distance between those venerable rivals from everyone else is eye-opening; the Yanks trail the Sox by 6 1/2 games but are still 21 games ahead of the next best interleague performer--shockingly enough, the often-underperforming Angels. (We've noted the teams who have most egregiously deviated from their overall performance levels by coloring them in blue--overachieving--and red--underachieving; we remind you here that the AL continues to hold an overall advantage in interleague play, though some of that is due to the oddly recurring vagaries of the interleague matchups, which have produced a higher percentage of good AL teams vs. bad NL teams over the years than random chance would suggest to be the case.)

The Red Sox are the major anomaly here, as a look at the scatter chart at right (25-year interleague play WPCT pinned with 25-year overall WPCT) will attest. The NL teams are shown in blue, the AL teams in yellow--with the exception of the Yanks (shown in navy blue), the Sox (shown in Red) and the Tigers (shown in green).A trend line on this chart would run pretty close to a straight diagonal from lower left to upper right--and that tells us that the Red Sox have consistently overachieved in interleague play (.596 WPCT compared to .548 overall for the year 1997-2022). The Tigers are the other outlier, albeit at a lower level due to their lower "highs" (fewer playoff appearances) and higher total of "lows" (a hefty handful of 100+-loss seasons). That invisible trend line would also reveal that the AL teams generally have overachieved in interleague play (most of them would be to the right of the trendline...and you can see the telltale separation between the blue and yellow dots).

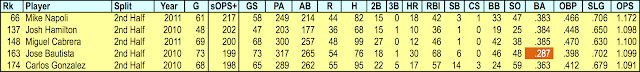

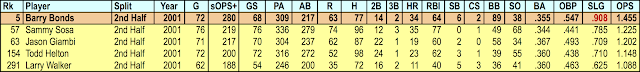

All of that is supposed to even out, right? Not necessarily--at least not under the original 15-18 game slice that comprised the original implementation of interleague play. The persistence of interleague competition patterns that created matchups between good AL teams and bad NL teams helped to preserve the AL's success, as NL teams who performed strongly in the first 13 year of interleague play (1997-2009) had shocking downturns in the second 13 years (2010-2002). Check out the Marlins (at the bottom of the chart below):