|

| At the end of May: SFG 35-15, LAD 34-15 |

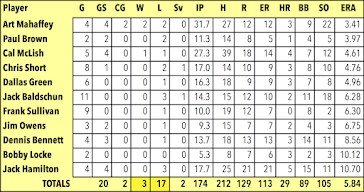

First, though...the updated results chart for May, keeping us glued to the tightening race. The two games played between the Dodgers and Giants (May 21-22, at Dodger Stadium) are shown in bold type. The games where both teams played in one-run games on the same day have a line box around them (yes, that one at the bottom of the figure is correct: the one-run games happened on the same day, but as different parts of a doubleheader).

The times that both teams lost on the same day are shown with red text: there are only two such occurrences during the month of May. (Note that we also highlighted the day where the teams played one-run games but had different results: that was on May 17, when the Giants lost to St. Louis 1-0 and the Dodgers edged the Colt .45s, 5-4.)

Some quick monthly team stat updates: after hitting .294 in April, the Giants hit .276 in May, averaging 5.5 runs per game. Their record for the month: 20-10.

The Dodgers, after hitting .259 in April, hit .291 in May, and averaged 6.1 runs per game. Their record for the month: 21-7.

After having a rocky start to their pitching in April (a 4.77 team ERA), the Dodgers snapped into form in May, with a team ERA of 3.03. In 264 IP during the month, they allowed only 14 HRs.

The Giants, who'd posted a team ERA of 3.15 in April when they jumped out to a 15-5 start, gave ground in May (team ERA of 3.65). They allowed nearly twice as many HRs in the month (26) as the Dodgers, in roughly the same number of IP. Some intimations of problems in their bullpen surfaced during the month.

ON May 31, 1962 (a Thursday), the Giants' Billy O'Dell was done in by his own error, which also involved an odd scoring anomaly. Reaching for a low throw from first baseman Orlando Cepeda, O'Dell inadvertently kicked the ball down the right field line, allowing the hitter (Tony Gonzalez) to reach base, and permitting the runner from second (Johnny Callison) to score. Ordinarily this would have been an unearned run, but there was only one out when O'Dell committed his fluke error and Gonzalez was credited with an infield single on the play (he'd actually beaten O'Dell to the first base bag). The next batter for the Phillies, Mel Roach, followed with a single, which would have scored Callison anyway. So it was scored an earned run, but no RBI--a very rare occurrence indeed.

That extra run was enough to hang the loss on O'Dell, for the Giants could not solve Art Mahaffey, managing just six hits, and mounting only a belated but futile rally in the top of the ninth, falling one run short. That snapped their seven-game winning streak. Final score: Phillies 2, Giants 1.AT the Polo Grounds, teenage monster Joe Moeller got a quick hook from manager Walt Alston, who must've had a feeling it was Ed Roebuck's day. Coming into the game in the fourth with the score tied 2-2, Roebuck threw five innings of scoreless relief, faltering only in the ninth when Alston tried to stretch him to the end of the game. By this point the Dodgers had built a 6-2 lead, mostly from a two-run triple from Larry Burright. (And we are not kidding when we say that the "Burright Era" will come to a sudden end within a week...)

In that overstretched ninth, two walks and an error on a possible double play ball by Jim Gilliam left the bases loaded for the Mets with no outs, but Ron Perranoski came in and induced former teammate (and recent nemesis) Gil Hodges to hit a grounder to short, where the Dodgers just missed a double play due to the ball sticking in Maury Wills' glove for a couple of extra seconds, allowing Hodges to reach first safely. However, the aging slugger pulled a hamstring trying to beat the throw, and this injury would keep him out of the Mets' lineup for an extended period of time. Perranoski retired the final two batters and brought home the Dodgers' thirteenth straight victory. Final score: Dodgers 6, Mets 3.

IN CONTRAST with that notably long relief appearance by Roebuck, we have the present-day relief pitching strategy, which often involves three or four pitchers who throw a single inning each. Remember when we told you a few weeks back that one of the reasons why run scoring levels were down was because the relievers were on a hot streak? (Even if you don't remember, just nod your head--that's a good reader.)

Such a strategy can work as long as the relievers remain consistently good...but of course they are human beings, and they slump, get hurt, or get unlucky (like Billy O'Dell above). The last two days in 2022 MLB have shown what can happen when a strategy turns into an albatross: relief pitchers on May 29-30 this year combined for an ERA of 5.09, about fifty percent higher than the ERA they posted in April. (There were no position players performing mop-up duty on these two days, so the stats were not distorted due to this increasingly popular practice amongst managers.) It was one of the hittingest Memorial Days in quite some time, looking more like something from 1996 or 2000: 42 HRs hit over 26 games, producing an aggregate .459 SLG for the day. (The relief pitcher ERA yesterday: 5.60.)

We'll keep an eye on this phenomenon and report on it periodically--the relief pitcher usage practice that managers have slavishly adopted might well be coming back to haunt them. Stay tuned...

.jpg)