Be aware from the outset that we are not endorsing the headline above as fact, or as acceptable opinion. If the home run marks achieved by Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds are considered excessive, it's due to the climate that was created by those in charge of the game and the backlash generated by the shattering of a number--60--that had become (and, judging by the the gut reactions of many...) somehow beyond sacrosanct.

Aaron Judge had a seriously great season in 2022 (with an iconic OPS figure of 1.111) that included a second half that flirted with all-time performance levels. He's been anointed by a vocal minority as the "authentic home run king" as much for how and where he broke the American League home run record as for breaking it itself. The trappings of his achievement are crucial to its acceptance. Consider: 1) He plays for the New York Yankees, the franchise that has "owned" the AL single season home run crown for 95 consecutive years; 2) his first name is the same as the man who broke the all-time homer record--Henry Aaron--and who did so respectfully, without displacing any of the single season marks that had become fetish objects in the minds of fans and baseball insiders alike; 3) the circumstances that evolved around Judge's pursuit of the AL home run record resulted in him doing so as "gently" as possible.All three of these factors smooth the way for the emotional acceptance of one more blow to the game's long-standing enshrinement of the number 60 as a kind of cosmic lodestone for its "worldview." None of those factors were in place in 1998, when McGwire shattered the home run record by hitting 70--or in 2001, when an arrogant, bulked-up black man (Bonds) followed McGwire's "ripped fabric" and brought the entire edifice down on itself. That wreckage was transferred by journalists and a significant subset of fans onto those two individuals, resulting in their ostracism from the Hall of Fame even as other "cheaters" have been enshrined.

It's part and parcel of a reactionary turn in America that has been in process for forty years, but that has gained a peculiar form of momentum since 2001, when two adjacent pillars of American might collapsed in a shocking attack on the nation's own home turf--a landscape that has been shielded and sacroscant from harm and invasion in the visceral beings of its citizens ever since the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. The unwritten rule is than only Americans could plunder, destroy and ravage the American landscape; the violation of this tenet led to an absurd "war on terror" that is still reverberating nearly twenty years later.

And the same is true in baseball. The game (and its analytical cadre) found ways to reinstitute home runs into an even more central role without the shock and stigma of the single-season record being constantly threatened. Fixated more than even on the long ball, the game sacrificed and attenuated other forms of offense as analysts began measuring hitting events via terms such as "exit velocity" and "launch angle." It's useful information, but it, too, has been fetishized and distorted into a grotesque form of "sabermetrics" that has always harbored paradoxical and contradictory impulses.

So Judge rushed up to the AL record with a magnificent spurt in late August that might be among the best two weeks of hitting ever seen in the game's history. From 8/22 to 9/22, he hit .430 (40-for-93), hit 14 HRs, slugged 957 (!), had an OPS of 1.503 (!!) and helped carry a floundering Yankees team once thought to be one of the great juggernauts of all time over a chasm that might have made them the team that suffered the greatest collapse in history. (The Yankees had gone 12-24 in their previous 36 games; Judge's Herculean performance aided them in going 17-10 during his "month on fire" and stabilizing what had begun to look like terminal free-fall.)

That spurt got Judge to 60 HRs--and then things shifted, slowed down, seemingly conforming to the need for a convenient, drawn-out cycle of media coverage. Judge's bases-on-balls percentage (BBP), which had been pedestrian by his standards during the first half of the season (11.3%), escalated exponentially in this phase, peaking in the final two weeks of the season, rising to above 30% during this time frame.

|

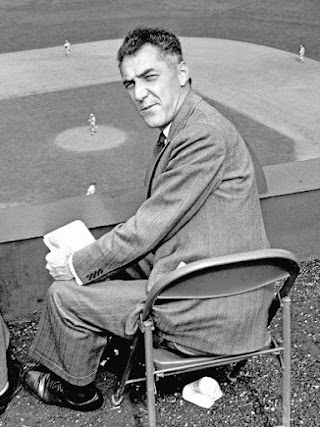

| Ford Frick has an asterisk for you, too... |

Judge hit #62 in the second-to-last game of the year, on the road (thus preventing the likely possibility of an unseemly stampede by a certain contingent of Bronx denizens) and, after getting one more at-bat, was summarily removed from the game by Yankees' manager Aaron Boone, who also kept him out of the final game the following day. One can always argue this both ways, but let's go here with the perspective that with the pressure of breaking the record removed, Judge had 6-7 more at bats that might have allowed him to put more distance on his Yankee ancestors. But for some reason, we'd come to expect that removing him at such a point was exactly what would happen whenever/if ever he set the record. And so it was.

It strikes me that, as things unfolded, it became silently understood and accepted that #62 would be the number, the extra notch, the break-but-not-shatter-and-destroy instrument of change. And somehow, through a mysterious but not entirely unexplainable set of circumstances, that's how things managed to come about. Breaking barriers and changing things shouldn't be too easy--unless there's a different type of fix in place, of course. (But that's the subject of a longer essay, in a different blog.)

Other little details that came to rest at the end of Judge's labors also tamped down the impact of his achievements. Cheerleaders for him to win the Triple Crown were (thankfully) thwarted when he struggled over the final two weeks; those who'd fetishized his count of total bases, looking for him to crack 400 and to possibly set a record for the greatest distance between his league-leading total and the closest also-ran, were also thwarted: he wound up with 391--a perfectly estimable total. These particular type of media folk, who bend and attenuate their own critical faculties to tailor their own public images, will eventually realize that it's much better this way, since it will make it easier to "domesticate" Judge's achievement, rather than have it stand out too much--which was precisely the "sin" committed by McGwire and Bonds.

We'll put Judge's achievement into a more comprehensive historical context--next time. Stay tuned...