Joe the P. is at it again...so here we are, once more cast in the role of the "truth police."

In his blog entry for Game 2 of the '22 World Series, the prose-y poser ledes with what seems like a startling stat: "Framber Valdez's outing was the first time in three years that a starter in the World Series went more than six innings!"

That stat is "true." It's not "inaccurate"--as far as it goes. But before one buys into Joe P.'s trailing thesis (pitchers and batters are better than ever yadda yadda but it's unfair that so many studly relievers can follow starters into games yadda yadda and that explains why hitting is down yadda yadda yadda--yechh!) let's examine this stat "that kinda blows your mind and also seems perfectly obvious at the same time":

--It covers a total of 27 starts in the World Series: 12 in 2020, 12 in 2021, and 3 this year.

--It doesn't take into account the totals/percentages in MLB as a whole, or in the rest of the post-season.

In short, it's a heavily massaged construction geared to distract you from the full reality of what's happening in baseball so that you'll swallow that trailing thesis, an argument meant to deflect from the fact that sabermetrics has led inexorably to the situation we're facing--a game dangerously close to succumbing to two-dimensionality thanks in large part to the execrable concept of the "Three True Outcomes."

In other words, Joe the P. is shilling for the quant quackers in order to give them enough cover to figure out a way out of the mess they've helped create.

Now Joe may have actually had a good answer for that in the rest of his piece, which isn't accessible to those of us who don't want to have to pay for his insights. (That's right, folks--we do actually draw the line somewhere...we won't pay to be shilled.) But based on all available evidence, we think it unlikely that he did so...because it's more fun to post an oversimplified stat than it is to gather a larger cluster of data that might actually reflect reality.

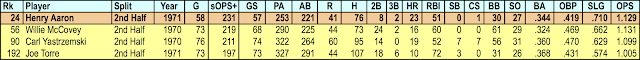

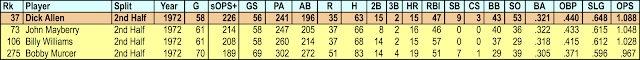

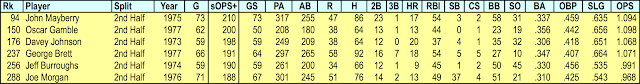

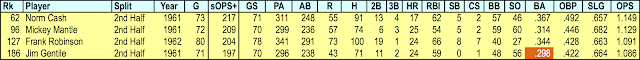

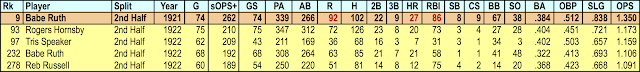

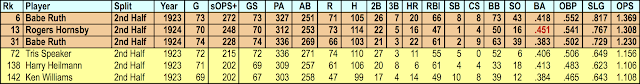

So here's reality, as reflected by how deep starting pitchers now go into games during the post-season. The chart at right breaks down IP lengths/ranges for starters over the past six post-seasons (we're still missing a few games for '22, but there's enough there at this point to be more than workable in context). The thresholds are: less than 3 IP (<3); 3-5.67 IP (>3<6), exactly 6 IP (6), and greater than 6 (>6).

How is that possible, given the "truth" of Joe P.'s "mind-blowing stat"? Who's smoking what?

Joe's smoking a brand called "selective sample size." His stat is for the World Series only, while ours is for the post-season as a whole. Prior to the '22 World Series, there have been 14 games in which the starting pitcher has gone more than six innings. That, added to Valdez' outing on Saturday night, works out to 21% of the starts in the '22 post-season.

There's no question that SP outings were seriously curtailed in 2020 and 2021. But that's not the case in 2022--the figures for 6 and >6 add up to more than a third of the total GS in the post-season (35%), a figure that's actually higher than than the six year average (30%).

It's interesting to see the flashpoint for short SP outings in '21--a set of results that would've been much easier for Joe the P. to have seized upon for his argument...except for the fact that it wasn't just a case of "openers" (though that notion appears to have spiked in '21). It was also a case where we had an inordinate number of poor outings from starters--including two from Framber Valdez in the WS against the Braves.

Now the uptick in longer outings just might push ol' Poser Joe back to his earlier argument--that starting pitchers are just too good these days. But that would have to take into account the fact that three of the four starts made in the World Series were sub-par performances by top pitchers.

Kinda hard to keep having it both ways--so best to lump them all together with a silly analogy about boxers, as Joe did in the part of the piece he was willing for the public to read. Which is worse--mixing incomparable sports or incompatible metaphors? We're not sure, but what's worse yet is doing both at the same time.

Next year will tell us if baseball has found a way to internally adjust for the "launch angle" revolution in a way that will prevent it from entering into a new variation of the "second deadball era" that continues to haunt the overwrought and overrated sentries of "baseball knowledge." Their theories and models laid the groundwork for what we've experienced in the past six years, and they are increasingly desperate to escape the blame for what they've helped create. Joe the P. is just the most voluble--and visible--of these folk. Take his provocations with a tablespoon of salt.