It was an off-day for both the Dodgers and Giants on June 21, 1962, so we return to our irregularly scheduled programming.

The topic of hot starts is here, of course, because the New York Yankees have been wiping the floor with their opponents for almost all of the 2022 season, causing shock, awe and dismay everywhere save for the Bronx. No one expected this, however--not even the Yanks' long-time GM Brian Cashman--but the rare occurrence of simultaneous good health for sluggers Aaron Judge and Giancarlo Stanton, a comeback season from Gleyber Torres, and serious top-to-bottom quality pitching (134 ERA+) over the first 66 games in the '22 campaign have this edition of the Bombers cavorting with the legendary, star-studded 1998 team. (Both posted 49-17 records over their first 66 games, and the '98 squad--as you may recall--went on to win 114 gams.)

As it turns out, hot starts are relevant to our coverage of the 1962 season as well, but for a more subtle reason than the fact that the Dodgers and Giants had exceptional success in the first two months of that year. But only one of those two teams meets the standard we're using for defining the term "hot start"--which is 66 games, in order to match up teams from the past more directly with the high-flying 2022 Yanks.

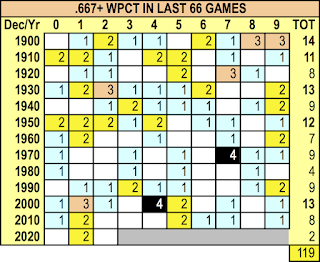

But there's also the flip side--the hot finish--which is less favored by the press due to the fact that they can't be projected into the future, they can only be captured at the season's close. There's no "added value" to the sportswriter or the "baseball analyst," because the story leaves no room for extrapolation (or embroidery).Thanks to our friends at Forman et fils (what we cheekily like to call baseball-reference.com), we know just how many 66-game "hot starts" there've been (defined as winning at lest two out of every three games through game 66 of any given season). It turns out there have now been 75 of them, what with the 2022 Yankees joining that club just recently. We can break these out by year using our patented "time grid" chart, and so we have (see it at right).

We're not going to give you an exhaustive rundown of which teams are on that list--we'll save that for another installment--but we will tell you that "hot starts" as a phenomenon have generally slowed down since expansion. Oddly, however, the 2019 season was the first ever to have three teams get off to a .667 WPCT (or higher) in the same year--those teams were the Dodgers (45-21), the Twins (44-22) and the Astros (44-22).

Hot starts do tend to cool off over time, but a sizable majority of the teams with hot starts have made it into the postseason. The average WPCT for a team that's made a hot start is .697, and their average WPCT at the close of the given season is .644, which is a bit more than an 8% decline. It turns out that the Pythagorean Winning Percentage (PWP) helps us (and all those other, panting media types) to predict more accurately the level of decline that will occur for "hot start" teams. The more distant the PWP is from the "hot start team's" actual record, the more that team is likely to decline. And that turns out to be relevant to our 1962 saga...but we'll bury that lede for awhile longer, and get back to the one we've been keeping buried for most of this essay.

What's that? Why, it's the "hot finish", silly. We wanted to ask you if you think there are more hot finishes (same 66-game slice, only calculated back in time from the final regular-season game) than hot starts, or whether it's the opposite (more hot starts than hot finishes), or whether the number is roughly equivalent to each other. Take your best shot at it now, because the answer (to take Satchel Paige slightly out of context...) is gaining on you.

So...as you can see, it's not even close. There have been almost 60% more "hot finishes" in baseball than "hot starts"--a total of 119 as opposed to the 75 "hot starts."(Now we know that some might object that such finishes aren't "hot" enough, that a higher WPCT and a lower number of games would be a better way to measure this. We'll just have to agree to disagree on that, because folks do not take a "hot start" seriously up until at least a third of the way through the season--thus it makes no sense to use a different benchmark for the back end of the season. And sometimes it puts things into a more normal perspective: for example, the 1969 Mets won 38 of their last 49 games, which is incredible--and incredibly rare. They went 45-21 over their last 66 games--a 7-10 start to a 38-11 finish, which puts them into perspective with other teams that had a more conventional route to that won-loss record. We need a larger population size for this phenomenon, so we increase the number of games in the "hot finish" to match the number of games where folks take the "hot start" seriously.)

Note that we've had two seasons where four teams had a "hot finish", both of them since expansion (1977, when the Yankees, Royals and Red Sox were in fourth gear in the AL, and the Phillies were cruising away from their competition in the NL; and 2004, when the Red Sox, Braves, Astros and Cardinals were wining at least two of every three games for the better part of two months).

There's much more to be written about this data set, but we're going to cut things off at this point and look for more open days in our ongoing coverage of the Giants-Dodgers 1962 showdown where we can interpolate more of this material into the interstices of that season-long effort. But before we go, let's return to the Pythagorean Winning Percentage and its usefulness in projecting what will happen to teams with "hot starts."

It stands to reason that a team winning more games than what's projected by PWP is likely to fall back in the standings over the course of the year. This turns out to be on the money for the teams whose PWP for their 66-game skein is markedly lower than their actual WPCT. Remember when we said that "high achieving" teams lose about 8% of their WPCT over the course of the year as their winning pace proves difficult to sustain? Well, the teams whose PWP diverges sharply in a negative direction from their actual won-loss record lost a bit more than twice as much ground as the average hot start team (-16.2%).

And do you know who has the lowest PWP of all the 75 teams with a 66-game "hot start"? That's right. It's the 1962 Los Angeles Dodgers, who were 44-22 after 66 games, with .594. That doesn't bode well for their World Series chances, now, does it? (But then you already knew that...)