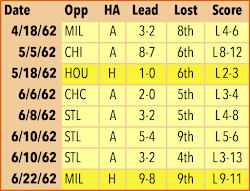

Thankfully, none of that was needed on June 30, 1962, when Sandy Koufax threw the first of his four no-hitters in Los Angeles against the New York Mets. Beginning the game with some of his best stuff, Koufax fanned seven of the first nine batters he faced, then struggled with his control in the later innings; he survived a rough eighth inning, where he threw a lot of pitches (losing his hat twice as he reached for something extra), and made it through on fumes in the ninth as two of the Mets slapped sharp grounders that just happened to be hit right at fielders.

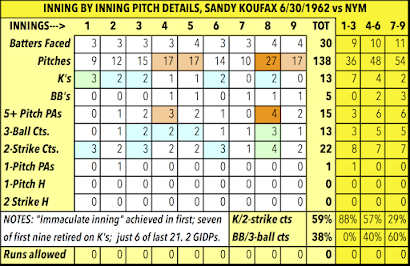

Thanks to the work of Allan Roth, we can anatomize Sandy's inning-by-inning progress on the road to his no-hitter, and create a display that might prove useful for locating in-game trends for pitcher performance. From what we know, only Roth was charting pitch-by-pitch information in 1962; thankfully, Retrosheet was able to obtain the data and incorporate it into their database, from which it migrated to baseball-reference.com, where it can be seen in what is arguably its definitive presentation. (Though we wish they had a chart like the one at left...)In this chart, we can see the inning-by-inning progression of pitches, strikeouts, walks, and other key "at-bat granular" stats such as three-ball counts, two-strike counts, one-pitch at-bats, high-pitch at bats, and hits on the first pitch or with two strikes. All of these variables can potentially tell us much more than the standard pitching line in a box score--or even such modern summary contraptions like Game Scores or QMAX.

When we use the data in this table, we see Sandy's blazing early innings, from the "immaculate" first (nine pitches, nine strikes, three strikeouts) through the third, where we can start to see some deterioration in his level of mastery (note the 3-ball counts creeping up in the third and remaining prominent in the innings that follow). The dominance can be further quantified with a look at the "K/2-strike c(oun)ts" stat shown in the lower right portion of the chart where three-inning breaks (innings 1-3, 4-6, 7-9) are displayed. Koufax converted 88% of his two-strike counts into strikeouts in the first three innings; but, as you can see, that figure declines markedly as the game goes on.

Likewise, the "BB/3-ball c(ount)s" rise as the game goes on, until in innings 7-9 he's pitching at a deficit in terms of the ratio of this stat to the "K/2-strike" measure (29%/60%). Those numbers probably tell us that Koufax was fortunate to be facing the Mets instead of a stronger hitting team as he attempt to nail down his "no-no." (We'll take this up again later on when we look at his later no-hitters in a separate article.)

The Dodgers scored four runs with two out in the bottom of the first inning to essentially put the game away from the get-go, with RBIs from the two hitters who'd dominate the RBI race in the second half of the year (Tommy Davis, Frank Howard). Even the almost-forgotten Larry Burright, who hit .161 in June after his singularly hot May, had a hit in this game. Final score: Dodgers 5, Mets 0.

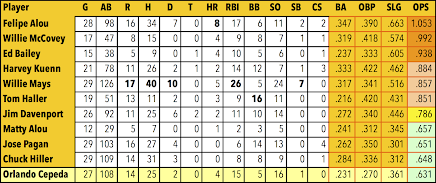

IN San Francisco, the end of June couldn't come fast enough for Orlando Cepeda, who had an extremely cold month (as the summary of Giants' hitters totals in June demonstrates). Felipe Alou, on the other hand, clearly wished that June could go on forever. Both of them observed the last day of the month with some longball action against the Phillies: Alou hit two homers and drove in four runs, including a three-run shot against Chris Short in the seventh. Right after Alou's second blast, Cepeda finished off a rare good day in June (3-for-4) with a homer of his own against Short.Bobby Bolin, stretched out by several long relief appearances earlier in the month, got the start and zig-zagged his way through 6 1/3 innings, in bend-but-not-break mode (9 hits, 2 runs). As the month came to a close, the Giants were looking like their old selves again. Final score: Giants 8, Phillies 2.

SEASON RECORDS: SFG 51-28, LAD 51-29