The poles of fame are, if you will, adulation and notoreity. The former rarely comes to anyone who goes out and seeks it, while the latter is often sought but seldom shed no matter how it becomes attached to that person. For Mark (the Bird) Fidrych, otherness (in the form of a gangly kookiness that brought out the variations of teenhood in everyone who encountered him or read about his exploits) was bolstered by sudden success. He became a national phenomenon in 1976, a year in which the USA was looking to put two national nightmares--Vietnam and Watergate--behind them and looked for something or someone that could restore some sense of innocence to their perception of things. (The previous year, the world of music re-embraced the Beach Boys more for their ability to embody the nostalgia that so many desperately sought: Fidrych, from Worcester, Massachusetts, was an East Coast update of that oddly articulated obliviousness that translated into white middle-class "cool.")

After his galvanic 1976 season, the Bird proved to be someone that things happened to, and that made the masses more sympathetic to his darkening plight. A knee injury did not prevent a triumphant return in June 1977, but a change in his pitching motion coupled with premature workhouse usage brought on arm woes that could not be overcome.

After his galvanic 1976 season, the Bird proved to be someone that things happened to, and that made the masses more sympathetic to his darkening plight. A knee injury did not prevent a triumphant return in June 1977, but a change in his pitching motion coupled with premature workhouse usage brought on arm woes that could not be overcome.Fidrych displayed no change in ego or personality at any point in his career; perhaps he was as surprised as the rest of us (including, perhaps, the insider baseball world) about his success and knew not to make too much of it. That trait endeared him to fans and more casual observers; they remembered that as much as the astonishing, improbable feats of 1976. An inaugural ballot candidate for the Shrine in 1999, the Bird received a healthy 24% of the vote in that first election and was inducted in his fourth year.

IN the case of Steve Dalkowski, extremity is almost too tame a term to describe what an outlier he was--a man whose exploits were so bizarre as to become instant fodder for the notoriety reserved for tall tales. A relatively small (5'10", 170 lb.) lefty, Dalkowski is notorious for three extreme things: speed, wildness, and a penchant for alcohol.

It's that last item that adds the darkness to his tale, of course. But his wildness was so extreme that it defies belief: think of our old friend Tommy Byrne and multiply by any number larger than two and you will understand. Byrne represented the absolute limit for a pitcher to be teeth-chatterlingly wild and still achieve success in the major leagues. (The "Power Precipice" region on our QMAX chart should be named for Tommy, just as its opposite region is named for his opposite number, Tommy John.)

Dalkowski walked a good bit more than a batter an inning during his nine-year minor league career, but he came tantalizingly close to the majors thanks to Earl Weaver, who while managing at Elmira in the Eastern League found a way to impart coaching advice that brought his skills more in line with the realities of the game. A freak elbow injury during a spring training game in 1963 proved fatal to Dalkowski's chances, and he fell back into obscurity.

But not for long. In 1970, Pat Jordan wrote the first of what became an avalanche of articles (that by now must number close to a thousand) about the strange, logic-defying exploits of Dalkowksi. Filmmaker Ron Shelton, who played in the Orioles' system a few years later and became entranced by the word-of-mouth he encountered about the fastest-but-wildest pitcher of all time, would begin the process that would culminate in Steve's enshrinement in the Eternals when he created a character for his 1988 film Bull Durham--Nuke LaLoosh (played by Tim Robbins)--who embodied many of Dalkowski's more legendary attributes.

This was quickly followed by David S. Ward's more overtly parodic Major League (1989), a massive box-office hit, which among its colorful roster of fictional Cleveland Indians featured a pitcher named Rick Vaughn (played by Charlie Sheen, who'd pitched in high school and purportedly used steroids to pump up his fastball) whose similar control issues earned him the nickname of "Wild Thing."

And so the Dalkowski legend passed into the great swirling swamp of mass culture, where it continues to produce ripples in the gurgling gasses that sweep through our collective semi-consciousness. In 1999, however, when the Reliquary began its Eternals project, Steve seemed to have slipped below the surface, gathering just 8% of the vote. But the following years were kind to Dalkowski, both in real life and in terms of his legend: his personal issues with alcoholism peaked and were resolved, resulting in "feel good" publicity and a re-visiting of his legendary on-field exploits. Reliquary voters took note, and in 2009 they ratified Steve's unique standing in baseball history.

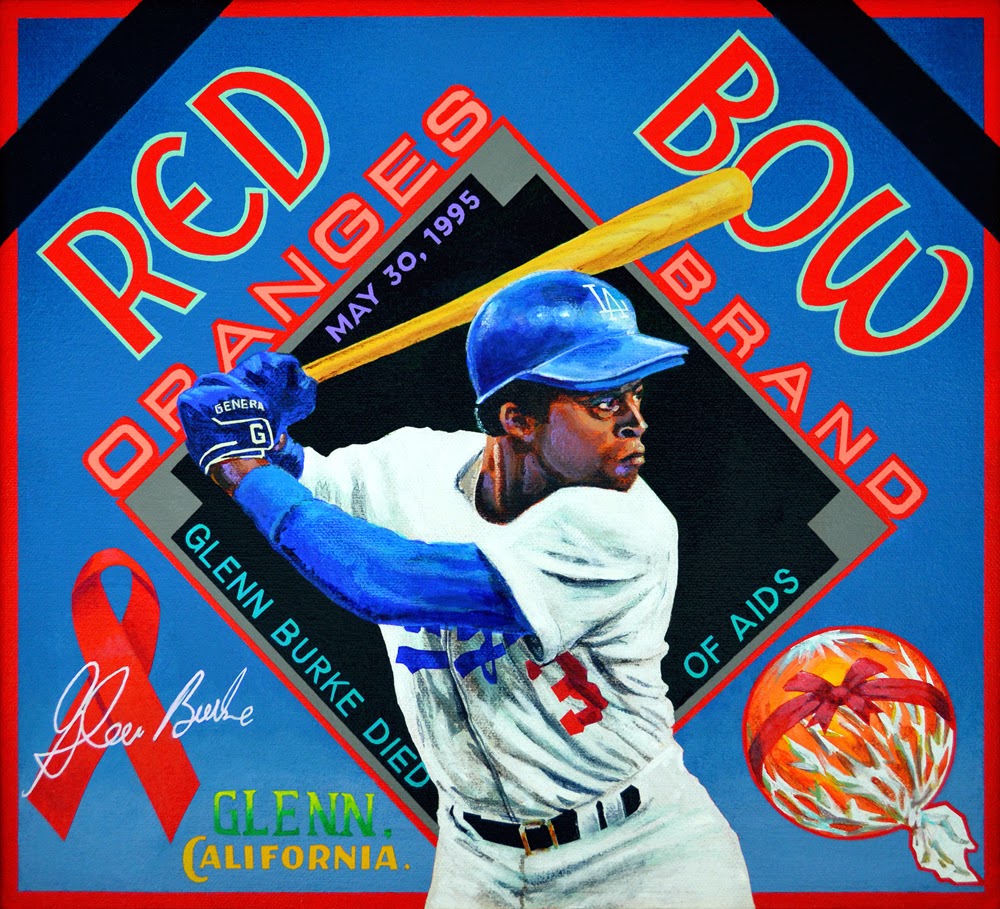

As is often the case with Shrine of the Eternals inductees, Ben Sakoguchi puts a little extra zip on his airbrush when it comes to pictorializing their exploits. For Fidrych, Ben plays with the fact that his nickname ("Bird") came from a coach who though Mark's wild blonde tresses were reminiscent of Sesame Street's Big Bird. (That same head of hair was instrumental in vaulting Fidrych into Rolling Stone as the embodiment of arena rock, which was just reaching its hysterical, excess-ridden apogee at the time.)

As is often the case with Shrine of the Eternals inductees, Ben Sakoguchi puts a little extra zip on his airbrush when it comes to pictorializing their exploits. For Fidrych, Ben plays with the fact that his nickname ("Bird") came from a coach who though Mark's wild blonde tresses were reminiscent of Sesame Street's Big Bird. (That same head of hair was instrumental in vaulting Fidrych into Rolling Stone as the embodiment of arena rock, which was just reaching its hysterical, excess-ridden apogee at the time.)For Dalkowski, Ben balances his lack of big-league success with the more upbeat tale of Rick Vaughn, who features indelibly in the Cleveland Indians' rags-to-riches arc in Major League. He does a fine job of adding a tinge of anxiety in Steve's expression, and he captures the eyewear linkage that director Ward had cleverly copped.

Ironically, Fidrych's life ended more tragically than Dalkowski (he was killed in a freak dump truck accident in 2009). Those are the vagaries of extremity and the unpredictability inherent in adversity, which can strike at any time. Otherness, however, knows no limits, and someone as caught up in its thrall as Ben Sakoguchi could not resist its siren-like call--as manifested by these two unique, but very different legends.